Nigeria Observations - Phase 1

This section is about Becky Paterson's (nee Smith) use of FLEx as part of her M.A. research at the University of North Dakota between 2003 and 2007.

Becky was an early adopter of FLEx at a time with SIL field method classrooms were still teaching Toolbox. FLEx is a much improved beast from use in these early years.

One of the tools which Becky used to conduct her research was to use the 1700 West Africa Comparative Wordlist to elicit words in a West Kanji language of Northwest Nigeria.

This work raises two important but separate issues. The use of noun classes to indicate plurality in FLEx and the use of unlicensed tools to create derivative works which do not credit the original tool or abide be the license of the tool.

Noun class as plural indicator in FLEx

At the time, and we are still (in 2017) dealing with noun classes in this beneue-congo language. The challenge is this: There is no specific way to mark the gender of the singular - plural pair. And in any given pair (where the default form might be either singular or plural) there is no clear and overt way to indicate what the other form is. We have settled on the following solution (which we feel is a bit less than elegant, because it does not help the researchers in the other related languages around where we are working).

Our solution has been to:

- add the noun class gender as a custom field containing both phonetic elements of the noun class gender.

- add the noun class gender as a custom field containing both numeric indicators of the noun class gender.

- add the plural citation form as a custom field

- add a custom field indicating if the default word is singular or plural

Some of these custom fields are a bit redundant, but by having them we reduce the number of factors needed to build filters on the database.

We have bascially followed the advice of Jeff schrum on this FLEx list thread:

Intergrating tools which are not overtly licensed

The second issue that has come up through our fieldwork has been the use of tools without a "proper license". The particular case comes from using the 1700 word SILCAWL. This resource was publicly published in 2004 as Snider, Keith & James Roberts. 2004. SIL comparative African word list (SILCAWL). Journal of West African Languages 31.2:73-122. journalofwestafricanlanguages.org. Now, there is a muddle of issues which I will try and talk through. These authors both have extensive experience working in West Africa. One of them was Becky's M.A. advisor, and we know them both personally. So, this critique is not a personal attack. The issue here is about giving legal freedom to do what is desired. This has not been a part of the historical publishing tradition, but now we have tools to do this so we need to use those tools.

These authors published with JWAL in a good faith effort to help not only SIL researchers, but also many other researchers, answer important linguistic questions. JWAL policy is that author's who publish with them retain copyright. Now if these authors were independent researchers they would own the copyright free and clear. However, these authors at the time of authorship were doing work for hire for SIL, and therefore were also bound by SIL's intellectual policy which allows authors to publish their work as their own publishing agent but states that SIL International retains the copyright of their work. Therefore even though JWAL policy reverts the copyright to the authors the actual copyright reverts to SIL International, not the authors. Later on in 2006 SIL's own publishing house republished the list as part of it Eletronic Working Papers series: https://www.sil.org/resources/publications/entry/7882. The SIL version from it's website does not carry an embedded license in the work, and at this time (2017) there is no clear statement from the SIL Publishing house stating under what license their works can be used or reused. So, we have an open access resource with a closed license or undeclared license. This means that full copyright defaults to SIL International.

According to standard interpretations of International copyright law, translations of a work count as a derivative work and are therefore also copyright the authors of the original work. (This is why we don't see a lot of commercially translated Disney films.) So this means that if linguists or organizations create translations of the 1700 SILCAWL then those works are also subject to be copyright SIL International. If these already presented facts obtain, which I assert they do, then this also should create concern to all those who use the 1700 SILCAWL as a starting point for their fieldwork and lexicography.

Since SIL's publication in 2006 Keith Snider has been working partially at Trinity Western University in Canada (TWU), and partially for SIL International. TWU hosts CanIL as their linguistics program. This Canadian organization is not SIL International and also hosts the Comparalex project (www.comparalex.org). This is a comparative look at various words across African languages. The intellectual property developed by CanIL belongs to CanIL. However, there is no clear indication that SIL has granted CanIL a license to use the 1700 SILCAWL or its derivatives - or has license the use of data provided to the project form SIL managed projects. This makes those parts of the Comparalex which are using 1700 SILCAWL and SIL International intellectual property subject to copyright infringement. This also means that other projects such as Conception http://concepticon.clld.org/ are also at risk of being in copyright infringment.

Now enter Becky into the story. Becky started her ut-Ma'in field work in 2005. In the process she pressed SIL's operations in Nigeria to translate the work into Hausa and Hausa Common Language (a pigin dialect based on Hausa). Becky as a early adopter of FLEx worked with Beth Bryson to get these Hausa translations into FLEx. This started a movement, the 1700 SILCAWL has now been translated into Portuguese, Swahili, Indonesian, and Chadian Aabic. It was originally published in English and French. All of these translated works are called into question on two grounds, 1) their explicit intellectual property creator of each translation needs to to also release their IP rights so that their translations can be freely used, and 2) SIL International needs to license the data portion of the 1700 SILCAWL in a way that it can be legally and freely used without making implications on the data collected by derivative user's data sets. (The license can not be a copyleft license like the GPL or like a Creative Commons ShareAlike license.)

I would normally advocate for the use of CC0, but in this case I am beginning to think that an opendata license may actually be a more fitting license, based on some of the other kinds of legal clauses.

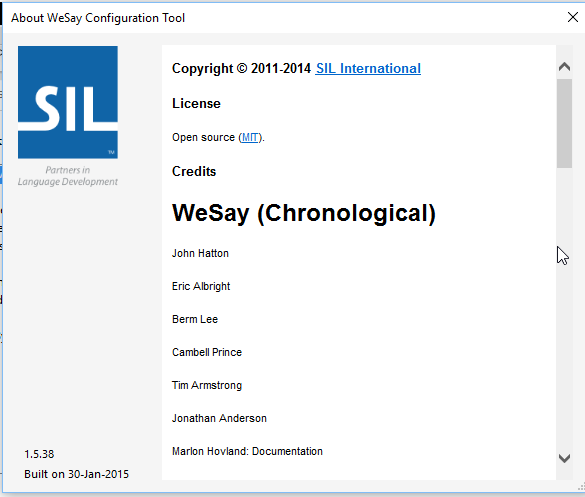

SIL's Software development team has incorporated the FLEx formated 1700 SILCAWL into its product WeSay (http://wesay.org), which it releases under the MIT license.

The unfortunate part is that the data set as an object should not be licensed under the MIT as this license is specifically designed for software. And within SIL, the software development team is not the responsible party for such data product licensing (or print media products).

So, if SIL International were to take the route of releasing the the 1700 SILCAWL it would free up other contributors (from within and without of SIL) to release their translations under the same license. At such a time as these translations are also released under a compatible license, then they can be merged into the data set and incorporated into projects like WeSay.

One remaining complicating factor with the nature of the dataset is that the dataset itself does not express the data license. That is, if one assumes that the 1700 SILCAWL is expressed as an XML database in the .LiFT format, there is no place in the current specification to say what data provided in the database is licnesed as (of course as a github project a license file could be added as an external file). I will return to this idea of incorporating the expressed license inside the database in another chapter when I talk about the onion model of licensing.